Panic attacks can feel like a medical emergency, even when you “know” you have anxiety. Racing heart, chest tightness, dizziness, numbness, shortness of breath, or fear of dying can be so intense that many people end up in the ER, only to be told the tests look normal. That experience is frightening, and it is also important information: panic is highly treatable with the right, evidence-based support.

This guide covers panic attack treatment options that actually help, both in the moment and over time, and how psychiatrists build an individualized plan based on a careful evaluation.

Why panic attacks feel so dangerous (and why treatment can work)

A panic attack is a surge of intense fear or discomfort that peaks within minutes and comes with strong physical symptoms. What makes panic uniquely distressing is the “false alarm” quality: the body’s threat system turns on when there is no external danger.

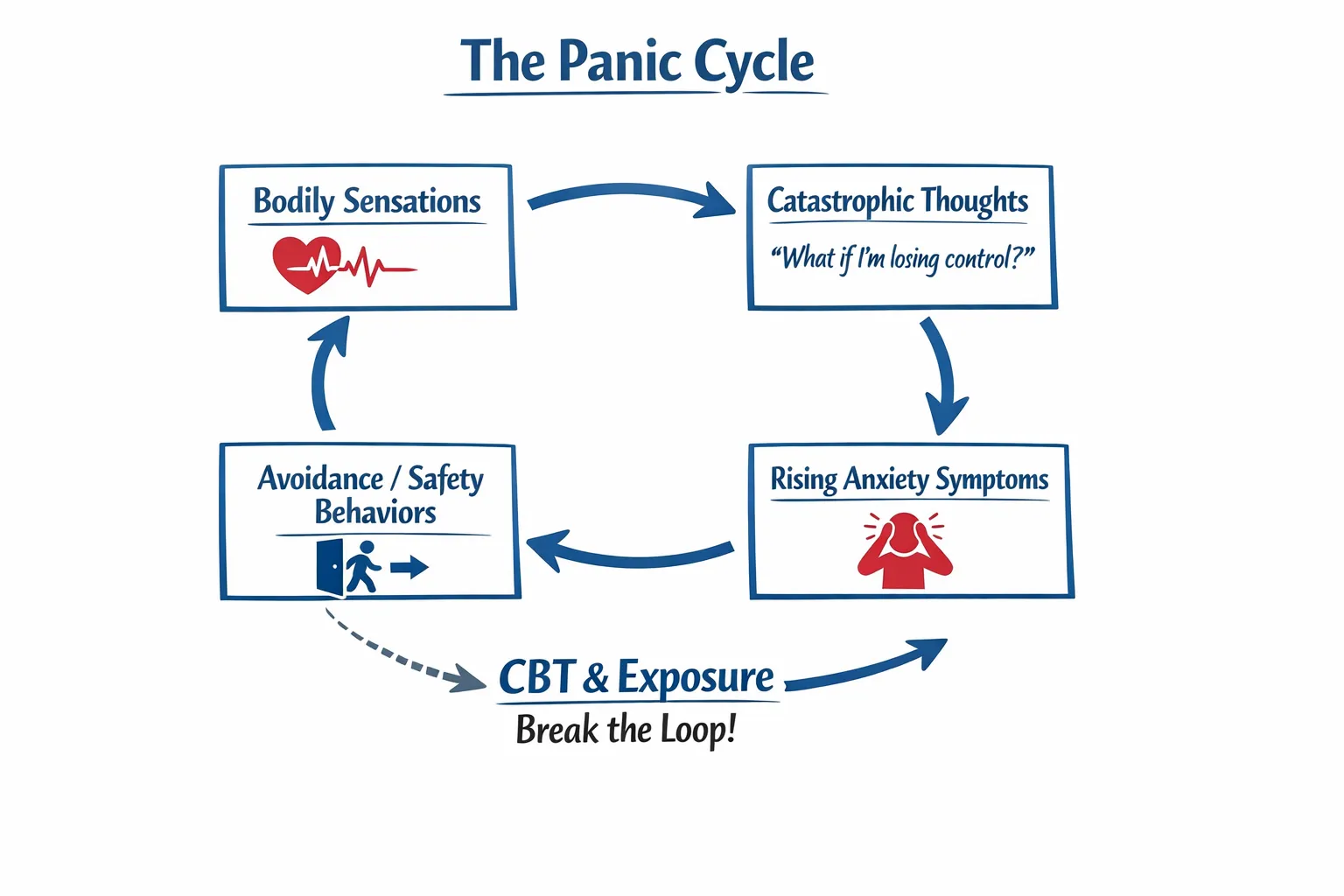

Many people get stuck in a panic cycle:

- A normal sensation (like a skipped heartbeat) is noticed

- The mind interprets it as danger (“I’m having a heart attack,” “I’ll pass out,” “I’m losing control”)

- Adrenaline rises, symptoms intensify

- The symptoms then feel like proof the threat is real

Effective treatment focuses on breaking this loop, reducing fear of bodily sensations, and changing the avoidance patterns that keep panic going. For a deeper explanation of how panic attacks differ from panic disorder (and when panic becomes a pattern that restricts life), see Panic Attacks vs. Panic Disorder: When a Scare Becomes Something More.

First step: make sure it is panic (not a medical problem)

Because panic symptoms can overlap with medical conditions, a good plan starts with a careful assessment. Depending on your symptoms, history, and age, your clinician may recommend medical evaluation to rule out contributors such as thyroid problems, certain heart rhythm issues, asthma, anemia, vestibular problems, substance-related causes, or stimulant overuse.

Seek urgent medical care (or call 911) if symptoms are new or unusually severe, especially if you have:

- Chest pain or pressure that is new, crushing, or radiates to jaw/arm

- Fainting, severe shortness of breath, or oxygen-related concerns

- New neurological symptoms (weakness, slurred speech, facial droop)

- A first-time episode where you cannot confidently distinguish panic from a medical emergency

Once medical emergencies are ruled out, treatment can focus more directly on panic, and many people improve significantly with structured care.

What can help during a panic attack (in-the-moment strategies)

In-the-moment tools are not a “cure,” but they can reduce suffering and reinforce a crucial lesson: panic sensations are intense, but not necessarily dangerous.

Slow breathing (to reduce hyperventilation)

Many panic attacks include subtle hyperventilation, even if you do not notice rapid breathing. This can worsen dizziness, tingling, and chest discomfort.

A practical target is slow, steady breathing for a few minutes:

- Inhale gently through the nose for about 4 seconds

- Exhale slowly for about 6 seconds

- Keep the breath low and easy (avoid big “gulping” breaths)

If counting increases anxiety, switch to a simpler cue: “soft inhale, longer exhale.”

Label the experience accurately (reduce catastrophic interpretation)

A small but powerful shift is naming what is happening:

“I am having a panic surge. My body is in fight-or-flight. This will peak and pass.”

Over time, reducing catastrophic interpretations can lower the intensity and frequency of attacks.

Grounding that engages the senses

Grounding can be helpful when the mind is spiraling. Try a brief sensory scan:

- Identify 5 things you can see

- 4 things you can feel (feet on the floor, back against the chair)

- 3 things you can hear

- 2 things you can smell

- 1 thing you can taste

This is not about avoiding feelings. It is a way to anchor attention while the surge crests.

Notice “safety behaviors” that can keep panic going

Many people unintentionally train panic to return by relying on safety behaviors such as repeatedly checking pulse, sitting near exits “just in case,” compulsively Googling symptoms, or avoiding any activity that raises heart rate.

A key part of evidence-based therapy is identifying these patterns and gradually changing them, so your brain relearns: “I can handle this without escaping.”

Evidence-based therapy options for panic

There is no single “one size fits all” approach. Psychiatrists typically look at your symptom pattern, triggers, avoidance behaviors, comorbid concerns (sleep, mood, attention, trauma), and functioning, then recommend options accordingly.

CBT with exposure (including interoceptive exposure)

For many people, one of the most effective psychotherapy approaches for panic is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that includes exposure.

Clinical guidance commonly recommends CBT as an evidence-based treatment for panic disorder. For example, see the UK’s NICE guidance on panic disorder.

CBT for panic is structured and skills-based. It often includes:

- Psychoeducation about the fight-or-flight response

- Identifying catastrophic predictions (for example, “If my heart races, I’ll collapse”)

- Testing predictions with planned exercises

- Building tolerance for bodily sensations and uncertainty

A core element is interoceptive exposure, which means intentionally bringing on safe physical sensations that you fear (like dizziness, breathlessness, or a racing heart) in a controlled way, then staying with them long enough to learn they are uncomfortable but not dangerous.

If you are comparing approaches, see CBT vs. CRT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Cognitive Remediation Therapy in Midtown NYC.

Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) when cognition is part of the picture

Some people experiencing panic also report “brain fog,” slowed thinking, concentration issues, or difficulty with planning and follow-through. In those cases, cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) may be considered as a skills-based, structured approach that targets cognitive functioning (for example, attention, memory, processing speed, and executive function).

CRT is not a replacement for panic-focused exposure work, but for the right person, it can complement treatment by strengthening the mental skills needed to function under stress and apply coping strategies consistently.

When testing helps: neuropsychological evaluation

If panic symptoms overlap with attention problems, memory concerns, learning differences, or significant workplace or academic impairment, neuropsychological testing can clarify what is driving the difficulty.

A neuropsychological evaluation can help:

- Differentiate anxiety-related concentration problems from other cognitive patterns

- Identify strengths and weaknesses across attention, memory, executive functioning, and processing speed

- Inform practical recommendations and targeted interventions (which may include cognitive-focused therapies)

Learn more in What Is Neuropsychological Evaluation?.

Treatment works better when you address factors around panic

Panic rarely exists in isolation. Vulnerability often rises when the nervous system is already under strain, for example with chronic stress, sleep disruption, high caffeine sensitivity, hormonal transitions, or trauma history.

Sleep is a common accelerator: insomnia increases baseline arousal, which can make the body more likely to misfire into panic. Evidence-based sleep treatment like CBT-I can be part of a broader plan. If sleep is part of the picture, see Can Sleep Heal More Than We Think?.

What an effective plan looks like (beyond coping tips)

Many people have tried breathing apps, mindfulness videos, or reassurance from friends and still feel stuck. Effective panic treatment usually involves a plan that is specific, measured, and progressive.

A strong plan often includes:

- A clear diagnosis (panic attacks, panic disorder, and any overlapping conditions)

- Identification of avoidance patterns (driving, subway, meetings, exercise, travel)

- Skills for acute surges (breathing, grounding, cognitive labeling)

- Exposure work that targets the exact fear (sensations and situations)

- Cognitive and functional assessment when attention, memory, or executive functioning concerns are present

- Follow-up that adjusts based on response, not guesswork

Getting help in NYC: what Comprehensive Psychiatric Services can offer

At Dr. Iospa Psychiatry Consulting, care is designed to be comprehensive and individualized, and all decisions are made by psychiatrists. Panic can overlap with sleep problems, mood symptoms, attention issues, and cognitive stress, so treatment planning starts with a thorough evaluation and may include psychotherapy referrals and coordination, and when clinically appropriate, neuropsychological testing and cognitive-focused interventions such as cognitive remediation therapy.

Care is available in Midtown Manhattan and via telehealth, which can be especially helpful if panic has limited your ability to travel or commute. If you are exploring support, you can start by reviewing the practice approach at Comprehensive Psychiatric Services in NYC.

A final note

Panic attacks are common, frightening, and treatable. Many people improve when care focuses on accurate diagnosis, evidence-based therapy options (including exposure-based CBT), and addressing contributing factors like sleep and chronic stress. When cognitive concerns are part of the picture, neuropsychological testing and cognitive remediation therapy can add important clarity and structure.

This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. If you are in crisis or think you may be having a medical emergency, seek emergency care immediately.