It usually starts with something small. You lose your train of thought mid-sentence. You reread the same paragraph and realize none of it stuck. You walk into a room and forget why you went there. For many people, moments like these raise a deeper question about brain fog vs cognitive decline. Is this mental overload from stress and poor sleep, or could it be an early sign of something more serious?

It’s an understandable concern. Awareness of dementia has grown, and stories about memory loss are everywhere. Even mild changes in thinking can feel unsettling. But in clinical practice, brain fog and cognitive decline are very different experiences, even when they feel similar at first.

The distinction matters. Brain fog is common and often reversible, especially when contributing factors such as stress, sleep disruption, illness, or treatment effects are addressed. Cognitive decline, by contrast, may signal a progressive condition that benefits from early recognition and monitoring. Confusing the two can lead to unnecessary fear—or delay an evaluation that could provide clarity and reassurance.

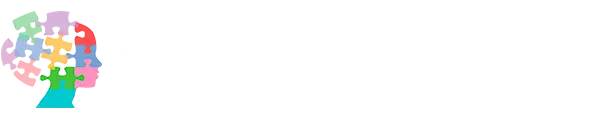

How Brain Fog vs Cognitive Decline Feel Different

Brain fog is best described as a change in mental efficiency rather than a loss of ability. People often say they feel mentally tired, distracted, or slower than usual. They may forget details because their attention drifts, not because the information is gone. Importantly, symptoms tend to fluctuate. Some days feel better than others, and many people notice improvement with rest, better sleep, or reduced stress.

Cognitive decline follows a different pattern. Changes are more consistent and tend to worsen gradually over time. Memory problems often involve forgetting recent conversations or repeating questions. Tasks that once felt automatic may take more effort. Over time, these changes can begin to interfere with daily life, work, or independence.

Clinicians pay close attention to this difference in pattern and progression. How symptoms evolve often matters more than any single lapse.

Why the Difference Between Brain Fog vs Cognitive Decline Matters

From a patient’s perspective, the difference affects both peace of mind and next steps. Many people with brain fog worry they are developing dementia when they are not. Others dismiss early cognitive changes as stress and delay seeking care.

From a medical perspective, the difference shapes the entire approach to evaluation and treatment. Brain fog often points toward factors that can be treated or modified. Cognitive decline raises different questions and requires closer follow-up.

Understanding which pattern fits helps ensure the right response—reassurance and targeted treatment when brain fog is likely, and timely evaluation when cognitive decline is a concern.

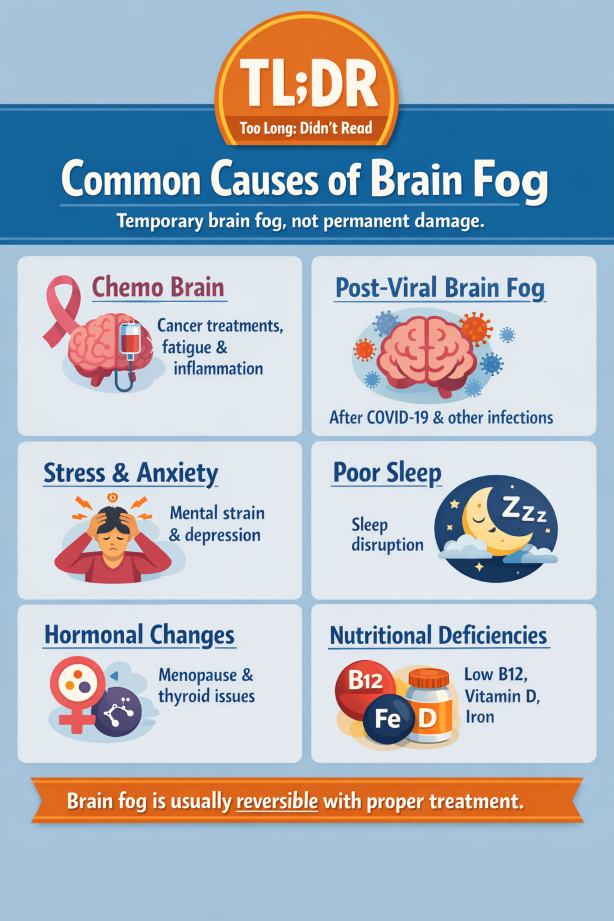

Common Causes of Brain Fog

Brain fog is often linked to conditions that temporarily affect how the brain processes information rather than causing permanent damage.

One well-recognized example is cognitive changes related to chemotherapy, often called “chemo brain.” People undergoing or recovering from cancer treatment may notice difficulty concentrating, slower thinking, or short-term memory problems. These symptoms can be distressing, but they are usually related to treatment effects, fatigue, sleep disruption, and inflammation rather than progressive cognitive decline. For many patients, symptoms gradually improve over time.

Post-viral brain fog has also become more widely recognized, particularly since COVID-19. Some individuals experience lingering problems with attention, memory, or mental clarity weeks or months after infection, even when the initial illness was mild. Research supported by the National Institutes of Health suggests that immune and inflammatory responses may temporarily affect cognitive function without causing lasting brain injury. Recovery is often gradual and uneven, but improvement is common.

Other contributors include chronic stress, poor sleep, depression, anxiety, hormonal changes, and nutritional deficiencies. These factors can impair attention and cognitive efficiency, making individuals feel forgetful even when memory itself remains intact.

When Cognitive Decline Becomes More Concerning

Cognitive decline is more likely when changes are persistent, progressive, and interfere with daily life. Family members may notice changes before the individual does. Forgetting important information, getting lost in familiar places, or struggling with routine tasks are signals that warrant professional evaluation.

According to the National Institute on Aging, cognitive decline goes beyond normal aging when it begins to affect independence and daily function. In these cases, further assessment can clarify the situation and identify any necessary support.

A Reassuring Perspective

For most people, memory lapses and mental fog do not signal dementia. They reflect how closely thinking is tied to overall health and life circumstances. Paying attention without panicking allows people to move forward with clarity rather than fear.

When to Seek an Evaluation

It may be time to seek professional input if cognitive symptoms are:

Persistent rather than fluctuating

Gradually worsening

Interfering with work, relationships, or daily tasks

Not improving with rest or reduced stress

Many evaluations begin in psychiatry or neuropsychology, where clinicians assess how mood, sleep, stress, and cognition interact. When findings suggest a possible neurological condition, referral to neurology is an important next step. This collaborative approach helps ensure that concerns are taken seriously without jumping to conclusions.

Many people assume that memory concerns must be evaluated by a neurologist. In practice, psychiatrists and neuropsychologists are often the first to assess changes in thinking, attention, and memory, especially when symptoms overlap with stress, mood, sleep, or medical illness.

At D. Iospa Psychiatry Consulting, psychiatric evaluations may begin with psychiatrists such as Alla Iospa, MD, or Konstantin Nikiforov, MD, who focus on understanding how mental health and medical factors shape cognitive symptoms. Their role is often to help clarify whether concerns are more consistent with potentially reversible brain fog or patterns that call for deeper cognitive assessment.

When additional clarity is needed, patients may be referred for comprehensive neuropsychological testing with specialists, including William Lu, PsyD, Dana Haywood, PhD, Catherine Stolove PhD, or Yuka Cohen PsyD. These evaluations provide an objective picture of how different cognitive systems are functioning and often help distinguish brain fog from early cognitive decline. When results suggest a neurological condition, referral to neurology follows as part of a collaborative care approach.